Storytelling is a part of our cultures that deeply inspires and motivate us, as oral tradition has been passed down from generation to the next for thousands of years. We each have a story that has stuck with us all our lives and kept us accountable to our most genuine selves. Yet, storytelling can do more healing than we understand. When there is a dominant culture that takes over another nation’s ability to control their narratives, identities can be modified and erased from written history. But to combat this cultural genocide and take back identities and cultures of a colonized group, there must be a backlash in the form of narrative. Storytelling can be used to combat the Eurocentric imperialist culture that “erased” identities from existence. As stated, “Stories also become the method colonized people use to assert their own identity and the existence of their own history.”

One novel whose story has deeply modified the way I view the impact of narratives is Toni Morrison’s Beloved. This book discusses the ways in which begins a healing process for the African Americans who experienced traumatic experiences of extreme dehumanization during the years of slavery in the United States. The term, coined by Morrison, defines the reencountering of the past in physical or mental spaces. In Beloved, rememory takes the form of places and things that you can visit and that will continue existing in the memories of people who have lived them. Even if the physical place is gone, the rememory will remain in peoples’ mind. This term symbolizes a physical manifestation of things that have been lost or destroyed, especially in regard to a dominant Western culture. This concept of revisiting the past can be applied to colonized groups in other regions as well. In this article, I discuss how people in the Amazon have combated a dominating Western culture by manipulating stereotypical Amazonian tropes with stories of indigenous peoples and Amazonian myths.

Edward Said argues in his essay titled Culture and Imperialism how narratives are the ways nations reinforce their culture to themselves and communicate ideas to and about other cultures. A central point of his argument is focused on how the novel was critical to “the formation of imperial attitudes, references and experiences.” When there is a dominant imperialist culture that controls which stories get told, the perceptions about minority groups and cultures are adapted and modified to align with what the dominant culture chooses. In this same manner, Spanish and Portuguese imperialist powers molded perceptions about the Amazon during the age of the “travel narratives” by creating an idea of the Amazon as the “other.”

Mary Louise Pratt examines in her essay that through the travel writing of the Europeans, the narratives and tropes surrounding the colonized nations were established by creating the image of the “other” in opposition to Europeans. Similarly, Neide Gondim’s essay, , details the impact of the Scientific Revolution on the perception of travel and global perspectives. Specifically, this book discusses how the image of the Amazon was created through the “European imagination.” Through this analysis of travel literature, Gondim describes how Europeans mirrored ideals of unknown lands to contain resources and riches to make them wealthier than ever before. As the Europeans already had an idea of the natural resources and colonized labor they assumed to get out of travelling to the Amazon, their idea of what the land could offer was based off of preexisting notions.

Through the development of these preconceptions began the formation of the concept of the “Amazon,” a biodiverse rainforest that provided new natural resources, as well as never-before-seen flora and fauna. The specific images and essentialisms associated with the tropics, also known as “tropicality,” was first coined by Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre. According to , tropicalities “revolve around systems of thought where ideas of nature, human nature, history, culture, and civilization are played out in the creation of images, institutions, sciences, and discourses that shaped and continue to shape the logics of colonial enterprises, modern development, and even today’s environmental strategies.” The ways in which Europeans, such as Wallace or Bates, described the Amazon in their writings reinforced these cultural associations that stemmed from their own preconceptions.

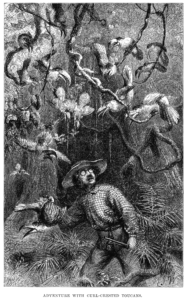

Representação de Henry Walter Bates na Amazônia. Fonte: WikiMedia.

Additionally, Mary Louise Pratt also dissects in her research the impact of travel writings today, and how the tropes and narratives that were created have influenced our thoughts and perceptions of the world of colonizers in comparison to the colonized. As Pratt stated, at the end of the eighteenth century, “Scientific exploration was to become a focus of intense public interest, and a source of some of the most powerful ideational and ideological apparatuses through which European citizenries related themselves to other parts of the world.” The revolution of travel narratives and natural science proved to be the catalyst for the movement centered around “planetary consciousness.” There was an importance placed on European history because the colonizers were the ones who got to control the narrative, and decide which “history” got recorded and which stories should be erased. A term Pratt coins is autoethnography, which suggests the ability for the colonized peoples, or the “other,” to define their histories and cultures in the terms of the colonizers. To be able to deconstruct the tropes established in the travel writings using the narratives and “autoethnographic” resources allows us to recognize the symbols that have been constructed that manipulate our perception, specifically in our case, of the Amazon.

One of the most renowned explorers of the late eighteenth century was Charles Marie de La Condamine, whose writings such as Brief Narrative of Travels through the Interior of South America (1745) circulated throughout Spain and the rest of Europe after his exploration. This text is a quintessential example of the type of travel writing that produced a Eurocentric perception of the “other” within the planetary consciousness. Brief Narrative included details on Amazon geography, flora and fauna, as well as the dangers associated with the region. La Condamine also conjectures on the location of one of the most famous tropes about the Amazon, the legend of the city of El Dourado. The legend of El Dorado symbolized the European dream of wealth and commodity. The promise of vast riches and unknown treasures motivated explorers for generations after the Amazon was first “discovered” by Western Europe, and its impact is still seen today. Although the real city of El Dorado was never found, and the myth of the lost city has long since been left behind, the essence of the trope still holds true in a modern-day exploitation of the Amazon. Therefore, in order to breakdown these tropes that have held true until today, there needs to be global introduction to the texts and narratives of the Amazonian people who have been directly affected by the harsh control of European conquest.

An Amazonian author whose works have reached global audiences is Milton Hatoum. His novels often subvert images and perceptions of the Amazon through meticulous descriptions of memory and depictions of nature. Through these masterful techniques, each story by this author offers an insightful lens through which to analyze Brazil’s history and the country’s struggle to define itself as a singular nation, especially concerning its relationship with the Amazon. In Hatoum’s book, , each of the characters represent versions of Brazil’s various past and current-selves, and gradually develop and unravel throughout the narrative. The most interesting aspect of this novel is the story of the narrator, Arminto Cordovil, and his relationship with the characters around him, especially Dinaura and Florita. The relationship between Arminto and these two indigenous women made a significant impression on his life, and is indicative of a larger allegorical application to the way in which a modern Brazil treats an “Amazon” on the cusp of modernity.

As the title suggests, the novel depicts the lives of those orphaned with the death of the legend and trope, El Dorado. This symbolic death takes its the form in the book with the shipwreck of the German freighter Eldorado, whose destruction ruins Arminto’s company and loses him all of his money, which is a big turning point in the progression of the novel. “I saw the Eldorado some hundred yards from the white palace, and then I thought my life depended on that cargo-boat plying the Amazon.” Before the crash of the ship, Arminto begins his relationship with Dinaura. However, after the one instance that they had intercourse, Arminto then decides that he wants “more” of Dinaura and cannot help but fantasize about their marriage and future life together.

Arminto’s obsessive and sexual attraction to be with Dinaura fulfils his legacy as the patriarch of the Cordovil family line by attempting to corrupt this image of a “virgin” Amazon. This desire for a simultaneous corruption of Dinaura as wealth and happiness directly plays into the death of the legend and dream of El Dorado. In this life-long search for Dinaura, her role as his fantasy-lover meshes with the idea of Eldorado, but reverts the original intention. As Rogers states in her book, , “For Europeans and Americans, finding wealth and happiness together remained an elusive objective precisely because the drive to enrich oneself by extracting the natural resources of the New World more often yielded strife than contentment.” Instead of becoming the physical representation for this idea of El Dorado, Arminto’s act of “deflowering” Dinaura coincide with the timely destruction of the Eldorado freighter and she becomes a manifestation of this desire for a modern version of the Amazon in which the El Dorado trope cannot hold.

Dinaura’s character does not make another appearance after the crash of the Eldorado. However, she feels present throughout the rest of the novel without being physically there. This presence mystifies and disillusions Arminto’s perception of her, especially when Dinaura is increasingly coupled together with the idea of myth and legend. “Dinaura had been seduced by an enchanted being… the place where she lived: a city with so much gold and light it gleamed… The Enchanted City was a legendary place, the same one I’d heard in my childhood.” Her sense of self becomes entirely melded together with the legend of the “Enchanted City,” and she loses any semblance of herself as an individual. In this disillusionment, Arminto realizes that in the search for Dinaura, the search for the “Enchanted City/El Dorado” is just as useless.

In the same way that Dinaura becomes this manifestation of sexual corruption to Arminto, their relationship is mirrored with Florita, an indigenous woman who was given the task of raising Arminto since childhood. She represents a past version of the Amazon who was used to “raise” the new version of white Brazilians who would just lead to same subjugation and exploitation of indigenous people. In this mirrored self, Florita and Dinaura become two sides of an oppressed Amazon: the first, exploited and forgotten; and the second, enchanting and mysterious. This version of a modern Brazil attempting to reconcile (and control) its relationship with an indigenous Amazon pervades this whole novella. As written in , “[Hatoum] exposes the attempt and failure of the Brazilian government to create a modern El Dorado.”

The legend of El Dorado and the Enchanted City are a critical part of this narrative. The importance of oral traditions is heavily emphasized in this novel. The style of writing and the form of the novel both directly play right into the aspect of storytelling to mimic the spoken tradition of the myth and legends. In Órfãos do Eldorado, the use of the spoken narrative meshes together the Western idealized, El Dorado, with the Amazonian myth and legend, the Enchanted City. By mixing these two stories, it once again tackles the way in which there is the forced reconciliation of a white Brazil and an indigenous Amazon. This novel portrays a deeply complex reality coupled with legend and fantasy to mystify the truth regarding the nature of a modern Brazil trying to manipulate its corrupt and oppressive relationship to an indigenous Amazon. With the death of the El Dorado myth, Hatoum addresses the future of both groups as they navigate new territory to solidify the core of the novel by ending with the line, “Do you think you’ve just spent hours… listening to legends?”

Narratives continue to reinforce our beliefs and perceptions of the world we live in. The way in which we deconstruct preconceived notions of the systems built around us should be through the resurgence of authentic stories from the cultures that colonized societies have attempted to erase. Beginning in the era of scientific exploration and travel writings, through the age of modernity, and the current modern day, the groups in positions of power in Brazil continue to exploit and manipulate Amazonian peoples for personal gain. The general collective must recognize the legitimacy of these Amazonian stories and fight for their voices to be acknowledged and heard.