Life is Wild

‘We have to stop with this fury of covering everything with asphalt and cement’

Click here and access the PDF edition of the text.

Translation by Marcos Colón

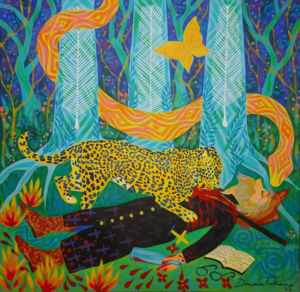

Life is wild. This is an essential element for a thought that has been provoking me: “How can the idea that life is wild be a concern of the production of urbanistic thought today?”. It is a summons to a rebellion of the epistemological point of view, of collaborating with the production of life. When I say that life is wild, I want to draw attention to a power of existing that has a forgotten poetry, abandoned by the schools that form the professionals that perpetuate the logic that civilization is urban, and everything outside the cities is barbarian, primitive – and that we can set it on fire.

How do we cross the city walls? What possible implications could there be between human communities that live in the forest and those that are enclosed in the cities? Because if we can manage to perpetuate the existence of forests in the world, there will be communities within them. I have seen the number that the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) published in a report, saying that 1.4 billion people in the world depend on forests, in the sense of having an economy connected to them. It is not the group of loggers, no, it is an economy that supposes that humans that live there need the forest to live.

The anthropologist Lux Vidal wrote an important piece on indigenous habitations, in which he related the materials and concepts that organize the idea of a balanced habitat with the surroundings, the Earth, the Sun, the Moon, and the stars, a habitat that is integrated with the cosmos, differently to this implant that the cities have become in the world. So, I ask myself how can we make the forest exist within us, in our houses, in our backyards? We can provoke the appearance of a forest experience beginning by contesting this urban sanitary order by saying: I am going to leave my backyard full of plants, I want to study it’s grammar. How can I find an Ipê tree in the forest, or a peroba rosa, or a jacarandá? And what if I had a moriche palm in the backyard?

The anthropologist Lux Vidal wrote an important piece on indigenous habitations, in which he related the materials and concepts that organize the idea of a balanced habitat with the surroundings, the Earth, the Sun, the Moon, and the stars, a habitat that is integrated with the cosmos, differently to this implant that the cities have become in the world. So, I ask myself how can we make the forest exist within us, in our houses, in our backyards? We can provoke the appearance of a forest experience beginning by contesting this urban sanitary order by saying: I am going to leave my backyard full of plants, I want to study it’s grammar. How can I find an Ipê tree in the forest, or a peroba rosa, or a jacarandá? And what if I had a moriche palm in the backyard?

We have to stop with this fury of covering everything with asphalt and cement. Our streams cannot breathe, because a catacomb mentality, agravated by a policy marked by sanitation, thinks that we have to put a concrete slab over any little stream, as if it were an embarrassment to have water running there. The sinuosities of the bodies of rivers is unbearable to the straightforward, concrete, erecting mind of those who plan the urban. Today, most of the time, urban planning is made against the landscape. How can we reconvert the urban industrial fabric into natural urban fabric, bringing nature to the fore and transforming cities from within?