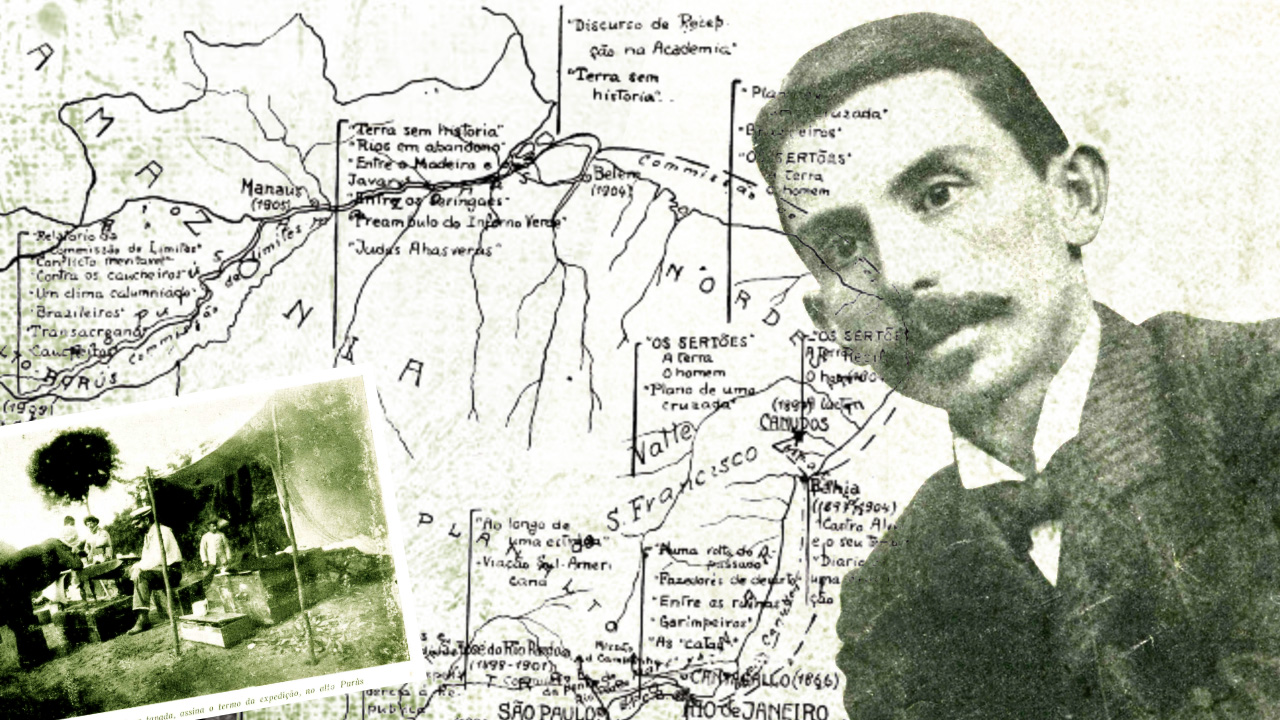

Storytelling, Care, and Abundance in ‘Stepping Softly on the Earth’

'This film is about the ecological systems that transcend national boundaries', said Professor Rob Nixon; Documentary by Marcos Colón was presented at the Princeton Environmental Film Festival

Kátia, chief of the Akrãtikatêjê people, during the filming of the documentary 'Stepping Softly on The Earth'.

Photo: Marcos Colón/Amazônia Latitude

On March 26, the film “Stepping Softly on the Earth”, by Marcos Colón, was presented during the Princeton Environmental Film Festival, at the Princeton Public Library.

The documentary was introduced by Professor Rob Nixon, the Currie C. and Thomas A. Barron Family Professor in the Humanities and the Environment.

It was wonderful to get a full taste of what I see as Marcos Colón’s Amazon trilogy. We had “Beyond Fordlândia”, which was very much about the incursion of rubber plantations into the Amazon a few years back. Today, we had the honor of seeing the second film in that series, “Stepping Softly on the Earth” and having viewed it twice, I just wanted to tease out a couple of the core concerns that I see in the film.

Starting from a comment that the Indigenous Brazilian shaman Ailton Krenak makes in the film, which is “the future is ancestral”, that may seem like a bit of a co- analytic that needs unpacking. The way I read it in the context of the film is that people who have been dismissed as belonging to the past may be able to provide some imaginative and ethical guidance towards the future.

And so, it speaks really to the imaginative endeavor of the arts, of storytelling, of image making, of understanding the future through the past. The Indigenous leaders who speak in this film share their critique of the ideas of development and progress that have brought them very little except ruin. So, that’s the broad-brush sense of “the future is ancestral”.

There’s another way in which Krenak is clearly talking about the ways in which, for their cultures to survive, they need to stay attuned to their ancestral ways. It is not that cultures cannot change because old cultures, like all ecosystems, are always in a state of flux. However, they cannot change at the speed with which change is being imposed on them.

And so, one threat in the film that really stood out to me was the threat of cultural assimilation. This isn’t about cultural purity or the idea of Indigenous cultures as noble, but simply the power of globalizing forces that are impacting these cultures. In one very grounded example, one of the leaders talks about how when she paints her face in the traditional manner, she feels empowered, but her children are embarrassed by the painted.

And in that moment of embarrassment, there’s a cultural wedge where she feels empowered and her children feel awkward, and maybe even disempowered. So, how do you maintain enough cultural continuity in the face of forces such as the mega ranches, the gold mining, and the deforestation that are changing the culture and the opportunities of the people who live there?

As becomes clear in the film, it was made under the duress of Covid. One of the ways that I think the film connects the idea of public health with ecological health in a way that is expressive of environmental justice values is the fact that these Indigenous communities in the Amazon suffered so many Covid deaths. They, in a sense, were afflicted with the worst of modernity in terms of the grain processing centers, the dredging of the river, and all these massive endeavors over which they have no control.

But when it comes to care, to hospital resources, they were denied. And so, those are the two phases of modernity, one of which has disempowered them and appropriated their lands and rivers, and the other, which they have been given inadequate and discriminatory access to. So, as I see it, the theme of care around Covid and the theme of care in relation to the environment converge in this film.

The idea of abundance, as one of the Indigenous spokespeople describes it, is connected to the idea of restraint. You cannot have the abundance of the forest without some cultural constraints on how much you can use that forest, and how much you must leave for future generations. The final point that I would like to make about this film is two things which really interested me. What really interested me was the fact that it’s about the Amazon basin, which is in Brazil, Columbia, and Peru. So, in a sense, this film is about the ecological systems that transcend national boundaries. This is also expressed in some of the visuals in the film when high, aerial shots convey a sense of the meandering of the river in relation to other visuals of many straight lines, such as the roads and the dredging of the river at its surface.

So, there are different visual perspectives in this film that express a rather brutalized linear progress as compared to the meandering of the river which has generously sustained Indigenous cultures.

I’ll leave it there. It’s a delightful film.