‘One of the greatest environmental damages in this decade is the armed conflicts’, said Ailton Krenak

At a screening of Stepping Softly on the Earth, Krenak issues a warning beyond concerns over climate change: ‘we should consider the possibility of extinction of a large part of the planet's life under threat from war and bombs’

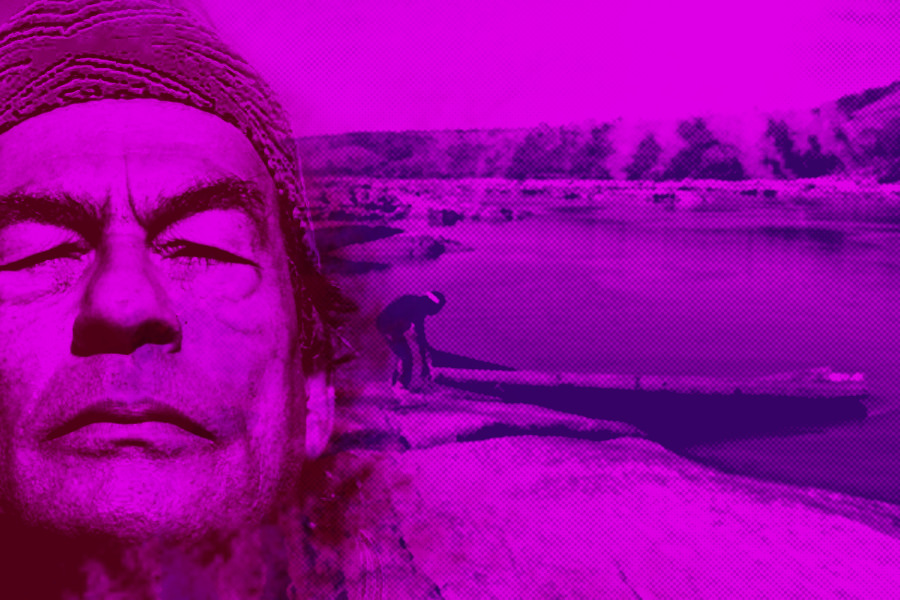

On October 30 2023, the documentary Stepping Softly on the Earth (2022, 73 min) was screened at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA). The session was followed by a conversation with the Indigenous leader, environmentalist, philosopher, poet, writer, and new member of the Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazilian Academy of Letters) Ailton Krenak, and the film’s director, Marcos Colón. In response to six questions from the audience, Krenak spoke for almost 30 minutes about what he called the ongoing contemporary dystopia on a planet immersed in wars, climatic emergency and capitalism.

The moderator, Susanna Hecht, from the Center for Brazilian Studies of UCLA, opened the conversation with a question to Krenak: What I would like to ask is if you can see a path, a way for us to get beyond this impasse we are in. We have climate change happening, and Brazilian government policies changing, but we see structural forces that are also very strong. So, how do you imagine and what strategies do we have for thinking about the future?

Ailton Krenak: So, it’s good to see you Susanna. It is good to hear you and remember that you have walked here in Brazil, walked in our lands, in the Amazon, and you saw how our people were at that time, living with a lot of self-affirmation and courage. And we go on the same way.

We know that we have a problem all around us, but we are strong and we are capable of translating this negative reality into something to better our position and affirmation.

Firstly, I would like to say hello to Marcos Colón who is there, and I can see him on the screen, and Alex Ungprateeb Flynn, who is also doing the interview. I also welcome everyone in the auditorium, Susanna, and I say that this contemporary dystopia is not limited to Latin America or to the Amazon rainforest. It is planetary.

Stepping Softly on the Earth was contextualized in the time of the pandemic, with great difficulty, when the future horizons were very bad. We were living in a pandemic and there weren’t many solutions. The documentary was made within a social nightmare. But it is a very beautiful film, because it shows that the people in the forest are also capable of creating other worlds.

We don’t depend only on the western narrative, we invent other worlds to live in. These health, political and global crises are disturbing people across the entire planet.

Us too, but we already have constant experience of changes, be it of the climate or economic. They always affect our way of life. And I believe that this brings more resilience to our people to face these difficulties.

So, Susanna, deliberating on the future may not be exactly what we need. It seems to me that what we need is an ever-changing world, an ever-changing world, not a future world.

For example, when we see a ruin, a forest ruin, we have to imagine that forest being rebuilt. A renovation.

This reconstruction is still possible in some parts of the world. We are in a place where we can rebuild. We have people that are living in a place that is already totally destroyed. They will have to escape from there; they are going to be refugees.

We are not refugees. Not yet. So, we have an ever-changing world.

I will continue because the thinking to accomplish the observations on imagining the future is to confront planetary dystopia. We are no longer living just a complex that we call climate change. It’s not only that. I am together with you at this time knowing that one of the greatest environmental damages that is occurring in this decade is all the armed conflicts.

In Russia, in Ukraine, Israel and the United States, there in the Persian Gulf; it is these wars that are punishing the global ecosystem. People keep talking about climate change, when, in fact, the heart of the issue today is the possibility of a generalized conflict in which we are going to damage the atmosphere of the planet, the terrestrial ecosystem, the oceans and many of our sources of subsistence are going to be affected by this sequence of irresponsible conflicts. And I still don’t see anyone including this as climate damage. If I could, I would propose a civil liability action against the governments that are dropping bombs and I would make them liable for environmental damages – not only for damages to human rights.

Ailton Krenak

Humans wage war all the time. Now, I want to make them liable, not for the deaths of other humans, but for the irreparable damage that they are causing to planet Earth, to the organism of the Earth and to the future generations, who won’t have the world that I had.

The future generations will have a world that is spoiled, a polluted world. And these authorities, these governments that are doing this, should be put in the dock, because they are infesting the planet.

It has nothing to do with climate change. It has to do with criminality. So, I am still waiting for someone to dedicate themselves to making an inventory of the environmental consequences of war, of this short period of war.

Let’s take the last ten years. Do an evaluation as to whether the damage is reparable or if it is irreparable. That’s the question. I want to see someone write about this or talk about this. Demonstrate the size of the environmental damage that the last armed conflicts have already produced.

If we are worried about climate change, now, we should consider the possibility that is the extinction of a large part of the planet’s life from the bombs.

Question from the audience: In what way do you think that we, with our voices, can still bring proposals or alternatives to this crossroads that, so to speak, we find ourselves at?

Krenak: Look, the common people, the commoners, throughout history, the commoners never have a voice.

And when they did the first climate report, that report called the Brundtland report – the other name of that report is “our common future”. When we were alerted to the fact that we would all become common, I mean, we are all going to be affected, we are all going to be attacked, we are all going to suffer the damage.

The issue is that not everyone has how to respond. The commoners don’t have how to respond. And the big corporations, the governments, these schemes, this substructure are the only ones that speak.

We, the commoners, regardless of how much information we have or not, we don’t have how to articulate a response to this crisis encased in various terms. It is a moral, ethical, political, conceptual crisis of principle.

In fact, it is a change of paradox. We need to change, I mean, of paradigm. We need to change the paradigm. It is all wrong. During the pandemic, people thought that everyone would die. Then, after, they invented that we would recover lost time.

I keep seeing that people don’t learn anything from tragedy. So, the commoner will continue without anything they can do. Especially now that this substructure decides everything and no longer needs this social conversation of popular participation.

That’s out of fashion. The authorities, the governments, make decisions and that’s it, together with the corporations. Whether it is about war or peace. Millions of people rose up recently protesting against the war.

I didn’t see anything happen because a few million people protested. Because those who have the power to make decisions are not listening to the people. They don’t listen. I really understand what you are asking me about the impotence of the commoner.

There was a time when if you had a multitude of people, you had strength. Now, if you have a multitude of people, it represents nothing. They have finished with citizenship. They have invented a global citizenship.

We are not citizens of anywhere. They are, in fact, producing a world of refugees. Everyone is a refugee. If there is a people that is still connected to their territory, they can transform their land into an identitary, a cultural power so it can live.

One has to practice cosmopolitics of the place where one is. It is what I do. I discovered what cosmopolitics is. Instead of continuing to have problems created by others, I create my own problems.

Question from the audience: I am an old disciple of Paulo Freire, one of the founders of the Paulo Freire Institute here at UCLA. I never understood why Paulo Freire became public enemy number one of Bolsonaro’s government. Because, as you say, that finished any chance of dialogue. Freire is a romantic, comparatively. Bolsonaro’s government used Covid as a weapon against the Indigenous peoples. It was obvious what he was doing. But now, what is Lula doing that is any different? That is really promising, as Paulo Freire would say.

Krenak: I believe that to answer your question, in the way of Paulo Freire, what Lula did was give back hope to the Brazilian people, especially with the ceasefire over Indigenous lands.

We started with Lula’s government ten months ago. He hasn’t been able to give much back, but he has managed to stop the attacks against the territories and the Indigenous peoples. That’s obvious, isn’t it? What he will be able to do beyond that will depend on the general situation.

Brazil is not separate from the global reality. Brazil’s economy is subject to the damage of a situation of general disorder on the planet. He is governing. And I hope he has conditions to continue governing.

Question from the audience: How do we get out of this state of coma we find ourselves in, how can we wake up?

Krenak: We can look at this from the perspective that Cólon mentioned, which is changing the food culture of the entire country, with 200 million people changing their food culture.

We can see this with other attacks on life, on the autonomy of small communities that have their territories dismantled for the production of a monoculture, which is the case of the Amazon and the Cerrado.

All these layers of violence end up making everyone a little sleepy, as if we were impeded from choosing another way, another possibility that is not this thing that is so predatory.

The possibility of us acting in relation to this involves an experiment, an exercise. The exercise is the body of the Earth. Body, Earth. The body has to be on the Earth, because if the body is on the Earth, it starts to receive extra-human stimuli, to receive stimuli from this thing we call nature.

But the person has to be plugged into the Earth. This plugging into the Earth – seek to do this wherever you are. Obviously, you can’t do this on a concrete sidewalk, but seek to do it.

If you are plugged into the Earth, you will see that Kátia Akrãtikatêjê, Pepe Manuyama, our other colleagues, our other comrades that face difficult situations on their lands, they continue to be strong, courageous, because they are on the Earth, they cannot leave the Earth. This is important. Then our bodies stop being this neutral thing and become reactive. Our organism is an organism that reacts.

It is the Earth that does this to us. It is the Earth that can make our body reactive and not be with too many things in the head. Don’t let your head get full. Put your head at the height of your heart so that you vibrate with your heart.

Don’t be shocked by the noise of the world. The noise of the world will not stop. So it is to keep a thought that confirms you as a being capable of transformation.

Stay on Earth. If you ask the Earth, the Earth provides. There is a Quilombola, my friend, who published a book recently, Nego Bispo. His book has the title of “A Terra dá, a Terra quer” (The Earth Provides, the Earth Wants). It provides and wants to receive. The Earth provides, the Earth wants. If you stick yourself to the Earth, all is well.

Marcos Colón: Krenak, this question is also directed at you. And mentions that the film brings the dialogue between the process of mechanization of large-scale ventures, such as the impact of the Carajás railroad on the village of Kátia Akrãtikatêjê, in Pará, and the oil activity in Iquitos, in Peru, described by Pepe Manuyama. In what way is this plurality important in the telling of these stories?

Krenak: I followed the description that you made of these extractivist activities in the Amazon region and maybe it was an opportunity for us to invite everyone that is following our conversation to understand that capitalism, today, throughout the world, is extractivist.

It is not only the Amazon. It is extractivist. It takes fuel, it takes grains, it takes wood, it takes everything from the land.

We have reached the peak of the greed of capitalism. The greed of capitalism goes around eating the body of the Earth. Sometimes we set up a tragedy and, in such a case, for example, the destruction of the Amazon rainforest by burning or mining, we crystalize one example and forget that this is happening all around the world.

Extractivism is the final frontier of capitalism. I mean, what we thought was a sophisticated and complex economy, is, in fact, an assault on the body of the Earth. This is extractivism.

It is capitalism at its most voracious. It has no ethics, it has no morals at all and doesn’t care. That is the issue. We cannot keep framing history. The history is that capitalism is bankrupt, it is desperate, and now it is biting the whole world in the neck.

It lost whatever relationship it had with the idea of humanity. In fact, the idea of humanity has already been abolished. The way that governments and corporations deal with people’s lives, life isn’t worth anything.

Question from the audience: I would like to say thank you and say that having a documentary like Stepping Softly on the Earth is, for us, a chance to show the world what has been happening in our country. I would also like to say that the publications of Susanna Hecht on the Amazon are voices for us. So, I believe that a moment like this brings the chance to show the world what we are suffering. And I leave a short question. How have the Indigenous peoples been trying to resist the advance of monocultures? What are the chances of trying to fight against this hysterical being, the introduction of this agro that is so present in our country?

Krenak: The publications of Susanna Hecht continue to be up to date, including in relation to the death and resistance of the Indigenous peoples, who always valued what they have locally, strengthening their diets, ensuring that there is food on their land to not go hungry, ensuring that knowledge is associated with the diversity of the forest, which is our medicine. So these strengths, they are more than strategies of resistance, they are strategies that produce a response to each crisis that arrives.

The crises, for us, are not exceptions. The crises, for us, are products of this unequal relationship that we have to face every hour of every day, and they don’t happen episodically, forgetting that most people have more difficulty dealing with these damages than the Indigenous peoples.

Some years ago, I said that I didn’t know how the Brazilians, in general, would endure an anti-social, predatory government, but that the Indigenous knew how, because we always face this type of abuse of our freedom.

I realize that now many people are feeling attacked, but we have always been attacked. So, this makes us not give up on any of our choices.

Our choices are plural, they involve having the forest, having the river, having quality air to breathe, food. So, it is a simple perspective, so to speak, which does not involve any apparatus. We don’t need another currency, we don’t need any bullshit like the people think that it is necessary to have a currency, to have economic power, to have guns. This is all useless.

We are interested in this connection with the territory and that is why we fight for the demarcation of our lands. We don’t want demarcation of the territory because we want a tract of land, a farm, no. We are trying to protect the territories so that we continue having fish, hunting, food, health, so that everyone can live with a little more confidence each day, without the false guarantees of progress.

This foolishness of progress, development. Progress and development are two myths totally without any foundation. They are bullshit. Progress and development: two falsehoods.